“Regulations for Our Black People”: Reconstructing the Experiences of Enslaved People in the United States through Jesuit Records

Kelly L. Schmidt

Loyola University Chicago

Originally published: March 1, 2021

DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2019.12

In the Jesuit Archives and Research Center in Saint Louis, Missouri, there are only two folders labeled “Slaves, Slavery.” One is housed in the Saint Stanislaus Collection, which contains records of the Jesuit novitiate and farm in rural Florissant, Missouri, near Saint Louis. Five items are inside: three tax forms listing the number and value of people the Jesuits owned, one receipt recording the hired-out labor of an enslaved man named Isaac, and a calculation by a Jesuit of labor time gained by increasing bondspeople’s work day. The other “Slavery” folder is part of the Saint Louis University Collection. It contains only two items that actually pertain to slavery: bills of sale for Mary, whom the Jesuits of Saint Louis University purchased in 1850, and Margaret, whom they purchased in 1862. Yet in over three years of research on the lives and experiences of the Jesuits’ bondspeople in Missouri and in the central and southern United States, my colleagues and I have unearthed hundreds of pages of documentation about the enslaved adults and children whom the Jesuits owned between the Missouri mission’s founding in 1823 and the abolition of slavery in 1865. They are not filed, labeled, or tagged as pertaining to slavery, for enslaved people were not the priority of Jesuit recordkeeping. Jesuits’ penchant for detailed recordkeeping, however, has ensured the survival of many records about their own human property.[1]

Jesuits maintained accounts of the world in which they lived, making their records valuable not only in understanding the Society of Jesus itself but in learning about the communities with which the order interacted and the nature of those interactions. As enslaved people were not the priority of Jesuit recordkeeping, unearthing the experiences of enslaved adults and children requires looking in unexpected places for Jesuit records about slavery. Records about the Jesuits’ bondspeople exist beyond the enclosures of Jesuit archives, in university archives, archdiocesan archives, parish registers, and city, state, and federal records. Thus, in addition to looking in unexpected places within Jesuit archives, the contents of Jesuit archives need to be put in dialogue with other archives’ holdings to help fill the silences. Though the Jesuits left little description of the individual lives of the bondspeople they owned, by cross-referencing these records—and by comparing them with other literature on the lives of enslaved people—we can begin to uncover what their lives in bondage were like.

This article reflects on Jesuit recordkeeping, reading against the archives, and finding stories beyond their scope in uncovering the experiences of enslavement by Jesuits in the United States. The global turn within Jesuit studies has seen sustained work on Jesuit slaveholding around the world over the last few decades. This paper focuses on one often overlooked corner of that world, the lower Mississippi River Valley in the United States in the early to mid-nineteenth century.[2] In so doing, it offers a methodology for reconstructing the experiences of enslaved people through the fragmented records kept about them in the archives of Catholic religious orders and institutions.

Jesuit Recordkeeping and the Archives

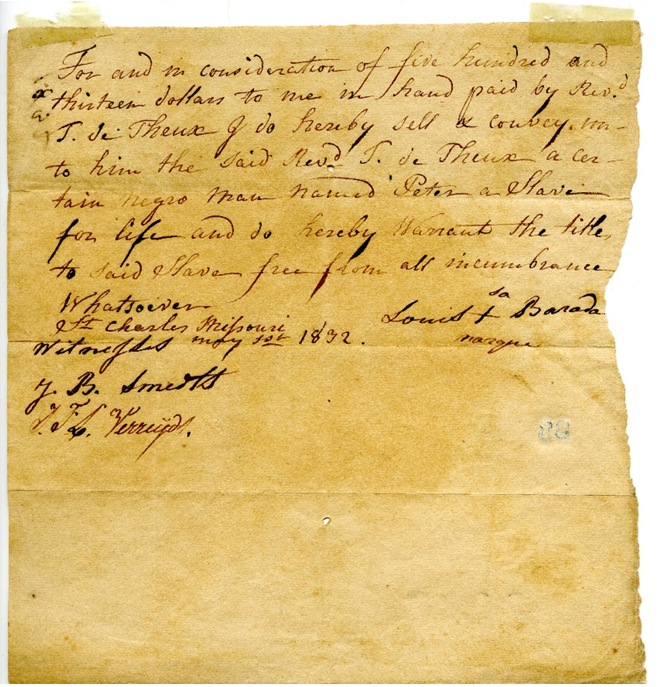

Although documenting the experiences of enslavement was not the intent of Jesuit recordkeeping, references to slavery and enslaved people are found in house histories, annual letters, financial and property records, sacramental records, correspondence, diaries, and memoirs established to record the history, governance, and daily operation of the Society of Jesus. Because the institution of slavery in the United States pervaded every aspect of American life, Jesuits would not have thought to “set aside” records about their slaveholding into its own category. Nor would this have been possible, since slavery was woven into the governing and missionary categories of their operation, shaping their financial accounts and religious ministries. At the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, one can find numerous references to enslaved people in a folder entitled “Bills.” Emancipation records for brothers Edmond, Samuel, George, and Thomas Tyler are located in a “Deeds” folder containing land purchase and sale information. A bill of sale for a man named Peter (perhaps by misfile, or perhaps intentionally) is in the middle of a file of Jesuit correspondence with the Office of Indian Affairs regarding Saint Regis Indian Seminary in Florissant. Sacramental records kept by Jesuits are filled with the names of people they held in slavery. Depending on the region, entries were arranged chronologically alongside white Catholics, or allocated to a separate register, segregated in print form just as people of color were often segregated in worship and society. The placement of these records does not demonstrate an intentionality to document enslaved lives; rather, Jesuits filed the records in this manner according to the way they ran their missions, schools, seminaries, and parishes. Jesuits demarcated and filed enslaved lives as markers of the fruits of their missionary efforts and as financial transactions, their ownership, sale, and emancipation filed in the same manner as land and other property.[3]

Figure 1. Bill of Sale for Peter, found in the “Office of Indian Affairs” folder in the St. Stanislaus Seminary Collection of the Jesuit Archives and Research Center.

To know where to look for records pertaining to enslaved people, and to understand their context, we must keep in mind how Jesuit archives, and Jesuit administrative units, have developed and changed over time. Archives of the Society of Jesus operate, in a sense, as both corporate and family archives: they house the records of a corporate body of a fraternal order of priests and brothers who live in community and believe in the renunciation of personal property and the ownership of all things in common. The order’s founders recognized the need to maintain frequent and consistent communication, regulated by regimented recordkeeping, to keep the widespread members of the global Society in contact. Ignatius of Loyola and Juan Alfonso de Polanco, the Society’s secretary and procurator (treasurer), outlined Jesuit practices of letter-writing to the Roman headquarters from Jesuit missions and houses, where Polanco maintained a systematic method of filing, annotating, responding to, and distributing letters. Loyola, who promoted the well-written edifying letter, encouraged members of his order to create multiple drafts of a letter before sending the final version.[4]

As Jesuits established missions and provinces across the globe, their systems of recordkeeping led them to create administrative repositories where they operated. When Thomas and Molly, Moses and Nancy, and Isaac and Susan were forced by their twelve Jesuit masters from the Jesuit White Marsh, Maryland, plantation in 1823 to help found the new Missouri mission, they were, without their consent, part of the expansion of the Society’s ministries—and recordkeeping—in the United States following the order’s global restoration in 1814. As a result, these three couples are present, though rarely addressed by name, and almost never referred to by surname, in the day-to-day correspondence, annual letters, triennial house histories, and regular financial reports their Missouri masters kept and reported to superiors in Maryland and Rome. As the Missouri mission grew into a province, their kin, some forced to Missouri from Maryland in 1829, their children, and other people the Jesuits purchased, appear in records stored in Missouri, Maryland, and Rome.

To find bondspeople in Jesuit records, one must understand the types and layers of these records, the purposes for which they were kept at each location, and how they were combined to be sent for approval and dissemination to central leadership in the province and in Rome. Each record had its own formula and purpose.[5]

Every Jesuit house was to be financially autonomous, securing local funding and reporting only debts to Rome. Each house kept daily financial accounts, which were distilled and compiled into province account books. An annual report of personnel, finances, and debts was forwarded to Rome. The status habitualis, or “state of customary affairs,” reported the number of Jesuit personnel, as well as those who served them, alternatively listed as auxiliares, domestici, or famuli (which can be translated as “the help,” “domestics,” and “slaves” or “servants,” respectively) in the Latin. Both enslaved and free laborers were included without distinction in the total; but when compared with other records, such as baptism and burial records and financial ledgers naming enslaved people, the status habitualis gives a sense of the number of bonded laborers at each location. In reporting the province’s major expenditures and debts, the status temporalis, or “state of temporal affairs,” occasionally gave an explanation in reference to enslaved people. Peter de Smet, procurator in 1862, recorded at the bottom of a status temporalis that the Jesuits had paid $800 for a “certain negro woman, whom one of our negro slaves was wishing to consider his wife.” From other Jesuit records, we know that their names were Peter Hawkins and his soon-to-be wife, Margaret.[6]

Jesuits at each house kept diaria, known as house diaries, or minister’s diaries. Diaria served as daily accounts usually written hastily in shorthand and incomplete sentences to document house financial matters to be referred to in later years to determine financial need. As Paul Shore has demonstrated, diaria keepers did not always express themselves uniformly; entries varied based on their level of experience, Latin proficiency, and the extent to which they offered their own personal commentary, reactions, or accounts of local occurrences.[7] The Saint Stanislaus house diary, for instance, recorded incidents in the lives of enslaved people, documenting births, deaths, and other significant events, such as the baptism of a man named Edmund by Edward Barron, a missionary priest who had recently been bishop of Liberia. However, in 1854, the recordkeeper ceased making note of bondspeople, despite the Jesuits’ continued slaveholding. Perhaps a new chronicler considered this information irrelevant, or perhaps a superior had directed that documenting enslaved people in daily proceedings was unnecessary. At Saint Louis University, the house diary acquired such a personal association that the record lost its recognition as the university diary in the archives’ catalog system and came to be referred to as “Francis Nussbaum’s Diary.” Nussbaum entered in 1857: “Evening studies finished at 7, so that there might be sufficient time after for the pupils to admire the dancing of the black slave.”[8] In the minister’s diary of St. Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, one can follow the Jesuits’ hiring of enslaved people from women religious and local community members, and the life events of the Jesuits’ bondsman Ignatius Gough, including his marriage, the births of his children, his punishment for damaging Jesuit property while inebriated, and his imprisonment for suspected involvement in an attempted slave revolt.[9]

Daily financial ledgers, house diaries, and sacramental records were typically combined into formulaic annual letters, or litterae annuae, circulated within and among provinces and sent by houses to provinces and provinces to Rome. Meant to give an overview of the main events in the house, province, assistancy, or Society of that year, and the Jesuits’ ministerial accomplishments, each paragraph served a specific purpose, such as numbering the sacraments, confessions, conversions, and Masses held in a given year, or offering obituaries for Jesuits who had died. Similar to how Paul Nelles describes “edifying letters” as a “mechanism for measuring evangelization,” a means for evaluating Jesuit effectiveness and proving the worth of Jesuits’ presence in an area, so, too, did annual letters document the “saving of souls enumerated in sacraments, mass attendance, confessions, etc.”[10]

What Jesuits documented in keeping with their own goals can be revelatory about the lives of enslaved people. In Missouri, annual letters often distinguished between white, black, and indigenous people when enumerating their proselytizing achievements. Every three years, such accounts were aggregated and delivered as the historia domus, or house history. Occasionally, notable events in the lives of Jesuits or the local community made it into these documents. Consequently, annual letters and house histories in Missouri have noted such things as the establishment of a “Negro chapel” in the gallery of Saint Francis Xavier (College) Church; documented considerations of how to respond to the abolition of slavery and employing the four families, now free, who remained on the Saint Stanislaus property; and provided a more robust account of Edmund’s baptism by Edward Barron than in the house diary and the confirmation records of Saint Ferdinand parish.[11]

As records passed through the Jesuit administrative hierarchy, the writers and reviewers of the records created multiple drafts, as Loyola encouraged, for revision and for distribution. Memoria were passed from local houses, to regional provinces, to the curia in Rome. Records often appear in duplicate in more than one repository as a result. The variations in drafts can be revealing. Shore and Markus Friedrich speak to how as records passed from local houses to the province, a provincial might edit out extra commentary in an annual letter made by a local scribe who did not know how to conform his account to the dictated structure, before forwarding the letter.[12] When the annual letter from Saint Stanislaus novitiate in 1869 reported the death of Proteus Queen-Hawkins, one version said Proteus “went on his journey toward a better life” while another struck the line and instead recorded that he “breathed out his spirit into the hands of the creator.”[13] Other iterations of Jesuit documents have even more significant differences in meaning. Thus, it matters when searching for information on enslaved lives to look in all the various drafts and copies kept in house, provincial, and Roman repositories for differences in commentary on enslaved people.

Repositories of Jesuit records multiplied as the Jesuit presence, slaveholding, and recordkeeping in the United States grew with the founding of new missions over the nineteenth century. French Jesuits of the province of Lyon accepted an offer to run Saint Mary’s College near Lebanon, Kentucky, in 1831. They delivered reports on their operation, and their enslaved people, to the Lyon province in France, and to Rome. When the Jesuits left Saint Mary’s College in 1846 to administer Saint John’s College (now Fordham University) in New York, documentation of at least seventeen enslaved people they owned went with them, the Saint John’s College diary picking up where the Saint Mary’s diary left off. Moreover, sites in the New Orleans mission operated by French and Missouri Jesuits since the 1830s became the New Orleans province in 1907, resulting in records mentioning enslaved people that were kept in Louisiana, Missouri, France, and Rome.

Post-restoration growing pains coupled with the challenges of adapting the Society’s governance to American civil, cultural, and business practices led to inconsistencies in Jesuit recordkeeping. Early Jesuit records reveal local variations of slaveholding practices in the United States, and the efforts superiors and visitors made to instill consistency across Jesuit missions and provinces that had adopted their own regional methods of managing enslaved people. Moreover, these records show how their slaveholding practices, and rules about documenting their slaveholding, changed over time—thus accounting for the absence and presence of certain records in the archives.

In the 1830s, Jesuit superior general Jan Roothaan (in office 1829–53) sent Visitor Peter Kenney to the United States a second time to regulate Jesuit practices. Kenney traveled in 1832 from Maryland to Missouri to observe Jesuit management of the mission, farm, and college and ensure practices were consistent with those in Maryland and Pennsylvania. As part of his visitation, Kenney advised reform in Jesuit recordkeeping and management of enslaved people.[14]

When Kenney visited Saint Stanislaus farm, he approved the customs book outlining regulations for enslaved people, commenting that he was satisfied with the Missouri Jesuits’ management of bondspeople, who exhibited “good conduct, industry, & Christian piety,” in contrast to complaints Kenney had heard from enslaved people on Jesuit plantations in Maryland. He credited the Jesuits for bondspeople’s good behavior, believing the Missouri mission could serve as an example to fellow Jesuits, and any Catholic, by preserving “every where the same paternal and yet vigilant conduct towards those creatures, whose happiness here and hereafter so much depends on the treatment they receive from their masters.”[15] Kenney’s quote is a reminder of the key rationale Catholics used to justify people’s enslavement in the early nineteenth century.

Yet Kenney admonished the Jesuits for transferring enslaved people as they saw fit between their properties, such as the novitiate and the university, without consistent documentation. He stipulated that, henceforward, there be a formalized sale between Jesuits for any bondsperson reassigned to a different property, in the same manner any two secular people would broker a sale. Thus, from 1832 on, we more frequently find archival records of bills of sale and financial transactions for exchanging bondspeople.[16]

Kenney’s efforts to codify management of enslaved people reflect his endeavors to regulate Jesuit administration and recordkeeping, including outlining in specific detail how Jesuits should keep their account books. Kenney required that each Jesuit house not only keep a ledger of daily accounts organized by date, with debits on one side and credits on the other, but also transfer them to a “general charge and discharge book” that organized transactions by category, so that expenditures and debts would be better synthesized and consequently easily reviewed and approved each year by the provincial. Each set of these house finances was combined into the financial ledgers of the mission (eventually, province) as a whole. Nelles explains that this precise, systematic accounting was needed to keep track of accounts across time and distance among the dispersed religious order.

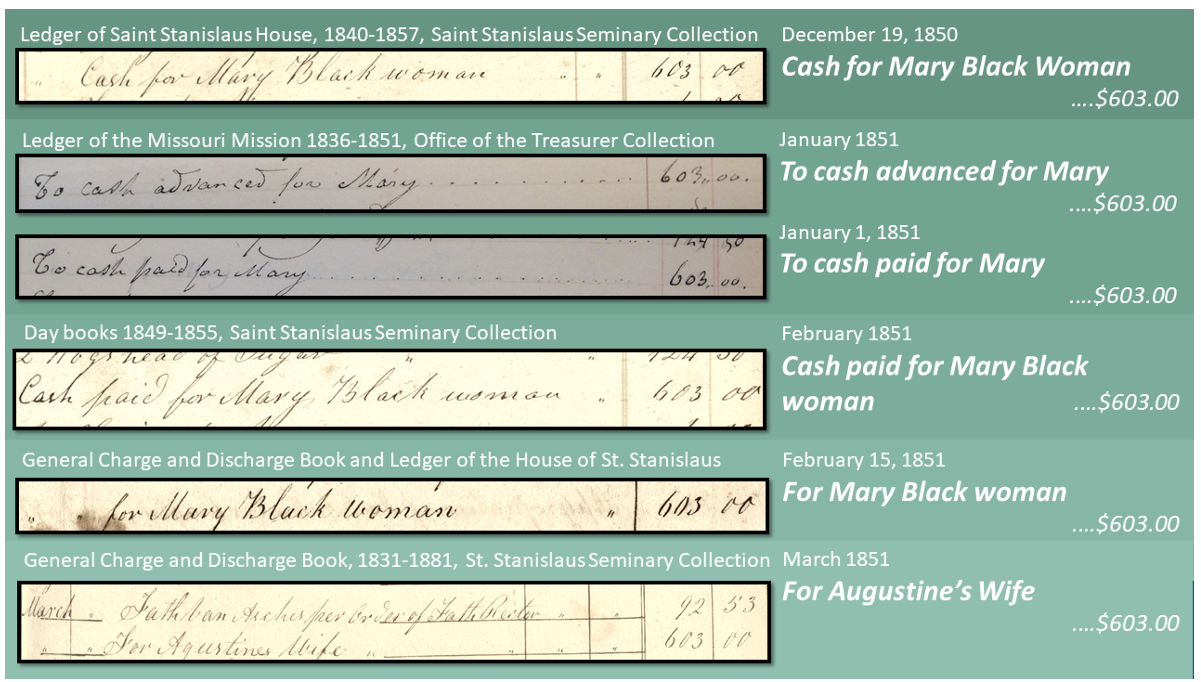

Houses were expected to charge one another for services rendered or resources reallocated between them because each was financially autonomous, required to obtain its own sources of income, and report its own debts. Due to Kenney’s reforms about the sale of enslaved people, and his specification on how to keep account books, financial transactions regarding enslaved people can be found repeated across mission or provincial account books. Thus, when Jesuits sold a man named Peter Queen from their novitiate at Saint Stanislaus to Saint Joseph College, which they ran in Bardstown, Kentucky, in 1849, the ledger of Saint Stanislaus house, the ledger of the Missouri mission, and the ledgers of Saint Joseph College all record the transaction. Likewise, when Jesuits used the money from Peter’s sale to purchase Mary Hoppins Queen, the wife of their bondsman Augustine Queen, her purchase was documented in the day books of Saint Stanislaus seminary, the seminary’s charge and discharge books, a volume entitled “Ledger of Saint Stanislaus House,” and the ledger of the Missouri mission.[17]

Figure 2. Records for Mary’s purchase shown across the account books of Saint Stanislaus seminary and the Missouri vice-province, housed in the Saint Stanislaus Collection and the Office of the Treasurer Collection at the Jesuit Archives and Research Center.

Kenney’s dictate also reflected changing practice in recordkeeping in adaptation to Jesuits’ American context. Similar to how founding Jesuits in the early modern period based the Society’s operation on Italian mercantile and ambassadorial practices, Jesuits, like other Catholic religious orders in the United States, had begun organizing themselves like corporations to conform with American business practices.[18] These adaptations shaped how Jesuit records identify ownership of enslaved people. For instance, although Jesuits considered themselves to own their enslaved people in common, one Jesuit, typically the superior, usually designated himself as the legal owner of all property, including human property. Thus, Peter Verhaegen “and others” appears as the entity named on behalf of the province and Saint Louis University in their tax records itemizing the worth of their enslaved people in the late 1840s and early 1850s.[19]

In addition to understanding how Jesuits historically structured and adapted their recordkeeping, it is important to know how archivists have reprocessed these records, seeking to maintain original order and filing schema, while at the same time organizing records in a manner that will be the most useful to those who need to refer to them. This calls for an understanding of the contours along which the Missouri Province Archives have developed. Early in the mission’s history, the superior at Saint Stanislaus passed a dossier of province records on to his successor. The superior kept a ledger listing the docket of deeds, financial records, and contracts transferred. While some of these ledgers and the contents to which they refer still survive, archivists have since reprocessed these files according to their category, such as finance or property, in accordance with the province archives’ system for arranging record groups, rather than keeping them in the superior’s files. As a result, a bill of sale for a woman named Mary listed in the superior’s ledger can no longer be found, its context having been lost.[20]

Originally, when the Missouri mission consisted of Saint Stanislaus and several churches and missionary outposts, most of the mission’s records were stored at the seminary and farm. As an extension of the Maryland mission, some early Missouri records went to Maryland and remain in the Maryland Province Archives. At some point after Jesuits took over the operation of Saint Louis College in 1829, provincial administration and recordkeeping appears to have shifted from Saint Stanislaus to the college. When Saint Louis University relocated from its downtown campus to its current site on Grand Avenue, the province records moved with it. They remained there until 1940, when the province records moved along with the provincial headquarters down the road from Saint Louis University to 4511 West Pine Boulevard. At some point between 1958 and 1968, “inactive” files were relocated to Pius XII Memorial Library on Saint Louis University’s campus and later moved to Fusz Memorial Hall. Saint Stanislaus seminary records joined the collections in 1971. In the late 1980s, the records returned to the province headquarters at 4511 West Pine Boulevard, and by 1997 the Wisconsin, Chicago, and Detroit province collections joined the Missouri province records, consolidating to become the Midwest Jesuit Archives.[21]

As Edward R. Vollmar pointed out in his 1968 outline of the relocations that alternatively split and combined records of the Missouri province, it has become challenging to locate original records without assistance and a sense of the historiography of these relocations. In the process of these transfers, records important for understanding enslaved experience have disappeared, such as the diary of Brother Charles Kenny, an overseer at the Saint Stanislaus farm who, according to Gilbert Garraghan, recorded intimate details about some of the enslaved people’s lives. Vollmar’s analysis points to the complexity of how records were housed by location or province, thus requiring one to look in multiple collections and repositories for the experience of enslavement at a particular site or within a particular region. Because at certain points in their early histories it was almost impossible to separate Jesuit administration of the Missouri province from that of Saint Louis University, especially since they shared the same personnel and frequently transferred enslaved people between the province’s seminary and the university, records became intertwined. As a result, attempts to combine and separate the records of each entity at various points in their archival history could not be cleanly accomplished. One can still find province records in the university archives and university records in the province archives. Thus, the first ledger of a volume documenting enslaved people may be within the province archives, while the second volume may be at the university archives.[22]

In 2017, the Midwest Province Archives became the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, the central repository for all the Jesuit provinces in the United States. As the Jesuit Archives has begun to consolidate Jesuit records in the United States, Jesuit provinces themselves have also been consolidating in recent years. Thus, what were formerly the Missouri province and the New Orleans province form what is now the Central and Southern province.[23] These changes in province and archives structure have resulted in patterns of splitting records similar to those of the Missouri province and Saint Louis University outlined above, because the records of Jesuit parishes and schools that are still running largely remain at the operating institutions, while other province records and collections of closed parishes and schools have been relocated to the Jesuit Archives. This means that ledgers recording enslaved people at Saint Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, which no longer operates as a college, are now located at the Jesuit Archives and Research Center in Saint Louis, while sacramental records for the same enslaved people are still located at Saint Charles Borromeo parish in Grand Coteau.

Reading against the Archives

Jesuits kept records for Jesuit purposes. The archives that retain these records are structured to reflect those purposes, with categories for finance, annual reports, daily proceedings, and consultors’ decisions. This means that what Jesuits recorded about enslaved people was what was important to Jesuits, for financial reasons, management, or religious motivations—not what mattered to bondspeople themselves. Reading “against the grain” compels us to reach deeper layers of meaning within the text by recognizing how structures of power have shaped surviving records, leading us to develop alternative interpretations of what the text can reveal. By recognizing hidden meanings and absent information within the bias lines of Jesuit perspectives and comparing these records with other sources on the lived experiences of bondspeople, we can reinterpret this material through the lens of enslaved people and begin to piece together what life was like for the men, women, and children held in slavery to the Jesuits.

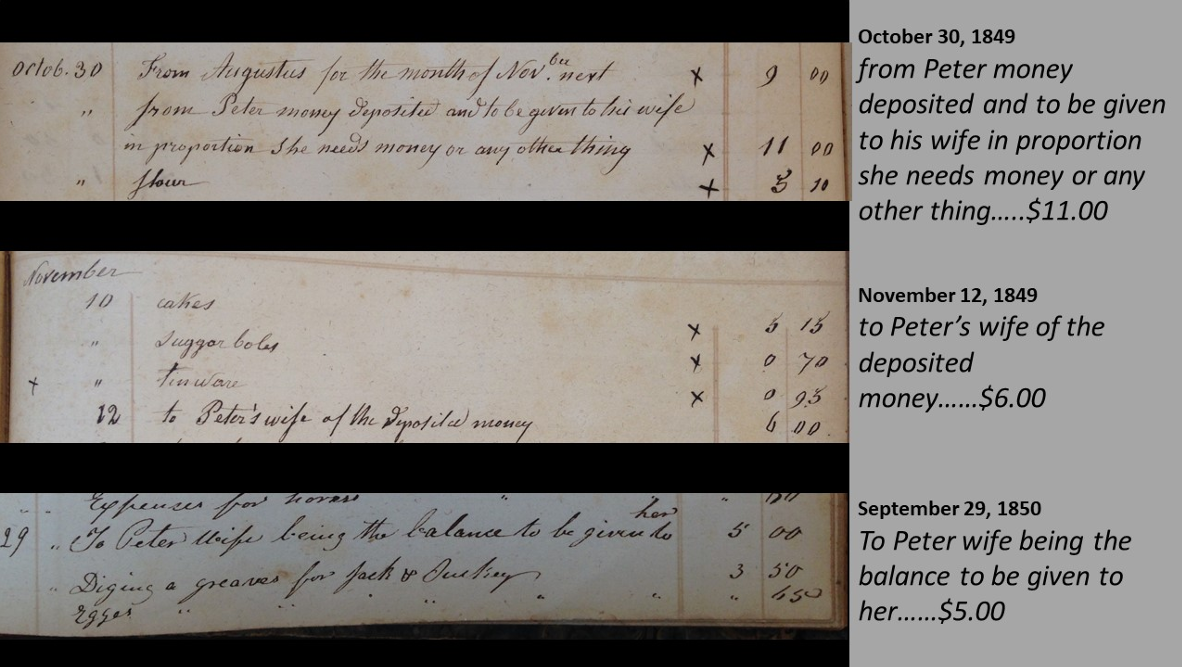

Let me suggest a few examples of this phenomenon. A Jesuit may list a bondsperson in a financial record simply to keep track of the order’s property and cash flow. But the same record can also reveal that enslaved people cultivated their own garden plots and sold produce to the Jesuits; that Peter Queen was sold away from his wife and young children; that another woman, Matilda Tyler, was paying installments to purchase her freedom. Jesuits tracked the number of conversions and sacraments they oversaw, in keeping with church dictate. But for the historian examining the lives of enslaved people, these records can help fill in information about family lives absent in other records, such as who married whom, and who were their children. In addition, they reveal patterns of kinship bondspeople had with enslaved communities beyond Jesuit plantations, through their choices of sponsors at sacraments.[24]

Figure 3. Other Jesuit documents record the sale of Peter from their seminary in Missouri to Bardstown, Kentucky. In the entries depicted here, Jesuits recorded the money Peter Queen left for the support of his wife, Marian, and three young children for financial purposes. Read from another perspective, these entries show Peter was torn from his family, despite Jesuit stipulations, and that Peter went to lengths to try to support them in his absence.

In addition to administrative, financial, and sacramental records, researchers can also read against the grain of Jesuit personnel files. Upon entering the Society of Jesus, men agree to join the Jesuit “family” and share their property in common. Thus, Jesuit archives retain personnel files that not only contain formal documents such as Jesuits’ vows but also often their personal effects, such as correspondence, diaries, writings, drawings, and photographs. Here, one can find rare but illuminating comments by individual Jesuits on the humanity of enslaved people, and discover glimpses of enslaved lives, even though this “family archive” is not structured to capture the key moments in their families’ lives. If a Jesuit’s personal papers show how he perceived slavery, reading against the grain leads us to consider his views from the perspective of enslaved people. When a Jesuit commented in 1851, for example, that enslaved people were “perfectly cared for, body and soul,” but an enslaved man, Peter Queen, was punished and sold to a Jesuit college in Kentucky, and then ran away within the same period, before being caught and sold away again as further punishment, possibly never to see his family again, we can discern the reality of bondspeople’s discontent despite any Jesuit paternalistic conceptions of their successes at slave-owning.[25]

By reading against the archives, we can seek out the lived experience of enslaved people. The early years in the Missouri mission were difficult for both bondspeople and Jesuits alike. All lived in cramped, inadequate housing, but while the Jesuits shared a large house, three enslaved families shared a small, one-room cabin with no loft that doubled as the kitchen and laundry. There remains little early recorded material on the management of bondspeople, which, according to Jesuit letters and memoirs, was inconsistent from the start and a source of constant consternation. Young Jesuits, including Felix Verreydt, Théodore de Theux, Verhaegen, and de Smet complained in letters sent to Maryland and Rome that their superior, Charles Van Quickenborne, was an inadequate farm manager and spent most of his time in the fields haranguing enslaved people when he should have been leading his fellow Jesuits in prayer. Van Quickenborne upset bondspeople to such an extent that other Jesuits documented the lengths enslaved people went to resist him, and the punishments that threatened them in turn.[26]

Reports by Visitor Kenney can be read against the grain to understand how Jesuits treated enslaved people, and how bondspeople used their knowledge of the system of slavery and the workings of the Jesuit order to seek redress. Due to reports of Van Quickenborne having an enslaved woman publicly stripped and flogged, Kenney urged that members of the mission heed Jesuit regulations on corporal punishment, outlining that no Jesuit should physically punish a bondswoman, or even threaten to do so. If a woman should need to be corrected, he wrote, a layperson could be employed to do it. Priests could not beat bondsmen, but novices and lay brothers could. Anyone, however, was permitted to give “slight correction” to youths under the age of twenty-one. Regarding housing for bondspeople, Kenney stipulated that “the visitor earnestly hopes, that the College of Saint Louis, will soon imitate the example given at the farm of the Noviceship by providing separate houses or chambers for each family of servants, and what is still more necessary, separate places for the unmarried males and females.” Despite these regulations, Missouri Jesuit records reveal that Jesuits repeatedly broke their rules on beating enslaved people and breaking apart families. Jesuit records frequently remarked on bondspeople’s inadequate housing, which proved a constant issue over the following decades. Even one letter from a bondsman, Thomas Brown, complains of his decrepit shelter.[27] Brown’s letter shows that he understood Jesuit communication and leadership structures, for he knew to write to Jesuit superiors in Maryland to complain of Saint Louis University rector Verhaegen’s neglect.

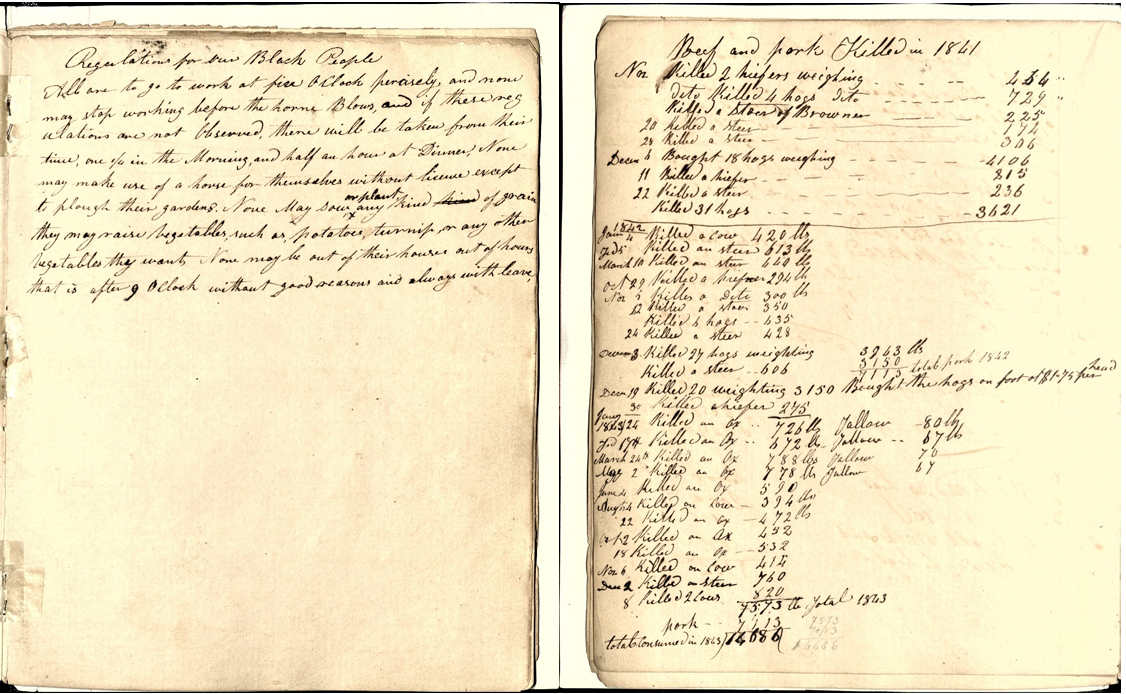

The regulations that followed in Kenney’s wake provide more opportunities for reading against the grain. After Kenney’s inspection, Missouri Jesuits codified their rules for enslaved people on a page entitled “Regulations for Our Black People” within a ledger called the “House Treasurer’s Inventories” in 1836. The list is followed in the ledger by stipulations for managing livestock. The regulations outline the hours of the day Jesuits expected enslaved people to work, and when they permitted bondspeople time off. It also describes monetary allowances granted for working on a day off or for doing a special task, such as breaking a horse. This excerpt stipulates when enslaved people could make visits or receive visitors, and states that they may not raise grain, but may raise vegetables such as potatoes or turnips in their personal gardens. By comparing this list with transactions pertaining to enslaved gardens, travel, clothing, and additional labor in financial ledgers, we can see how these regulations played out in reality, and thus begin to paint a richer picture of what life was like for enslaved people in a way Jesuits of the period rarely chronicled—both of the hardships they endured, and of the ways in which they surmounted their oppression and made individual choices within the confines of their bondage.[28]

Figures 4–5. Ledger page listing “Regulations for Our Black People.” The following page lists “Beef and Pork Killed in 1841.” Such records demonstrate how the Jesuits measured the enslaved financially and economically as chattel. The same records can be used today to reveal more about bondspeople’s human lives.

We are often disappointed when we approach the archives looking for a specific document about enslaved people because Jesuits did not prioritize documenting enslaved lives except when it mattered to their own goals. For example, what if we sought a list of the people owned by a Jesuit province, as many slaveowners often recorded in an inventory? Other than bondspeople named in transactions in financial ledgers, there are only two existing lists naming the enslaved men, women, and children whom the Missouri Jesuits owned at a given time. The first is found in an agreement stating that the Jesuits who founded the Missouri mission would bring six bondspeople with them, which names Tom, Molly, Isaac, Succy, Moses, and Nancy. The second list is in a ledger entry dated 1831, kept by the Missouri mission’s first superior for tracking the mission’s early finances and the properties the order had purchased.[29]

Figure 6. This graphic depicts how, by comparison with clothes distribution records and sacramental records, the list of names in this ledger was determined to be organized by family, with father and mother at the top of each unit, then sons in birth order, followed by daughters in order of age.

Neither source is definitive nor exhaustive, and they have more to reveal than what our first question asked. At first glance, there is no discernible order to the groupings of twenty-six names in this second document until they are compared with surviving booklets of summer and winter clothing distributions given to each enslaved family. Seeing who was included in each family group, and determining their approximate age based on the amount, size, and type of clothing they received, it becomes apparent that the groupings in the 1831 list are by family, with parents at the top, followed by sons and then daughters. As baptismal, confirmation, and Communion records for some enslaved people are located, they suggest that the children are listed from eldest to youngest. This aids immensely in identifying who bondspeople are when they appear in other records, especially when they share the same name. Through such records, we begin to glimpse what enslaved people’s lives and individual identities were like. By cross-referencing financial accounts, sacramental records, and governance reports spread across separate collections and different repositories altogether, we now know the surnames of those first six bondspeople, as well as the two enslaved families forced to Missouri in 1829: Thomas and Molly Brown; Isaac and Susan Queen or Hawkins; Moses and Nancy Queen; Proteus and Anny Queen or Hawkins; and Jack and Sally Queen.[30]

Beyond the Jesuit Archives and Beyond Emancipation

When using archives to understand the lives of individuals not historically deemed worthy of documentation and prevented by methods of oppression from being able to leave many written records of their own, looking beyond the intended scope by extending the time frame, repositories, and record types for review can reveal how enslaved families lived and thought even before they became free. Slaveowners’ records tend to obscure how enslaved people sought to use what means they had to take care of themselves and their own, and make meaning of their lives, but records from and about those whose lives extended beyond the abolition of slavery demonstrate how they exerted agency.

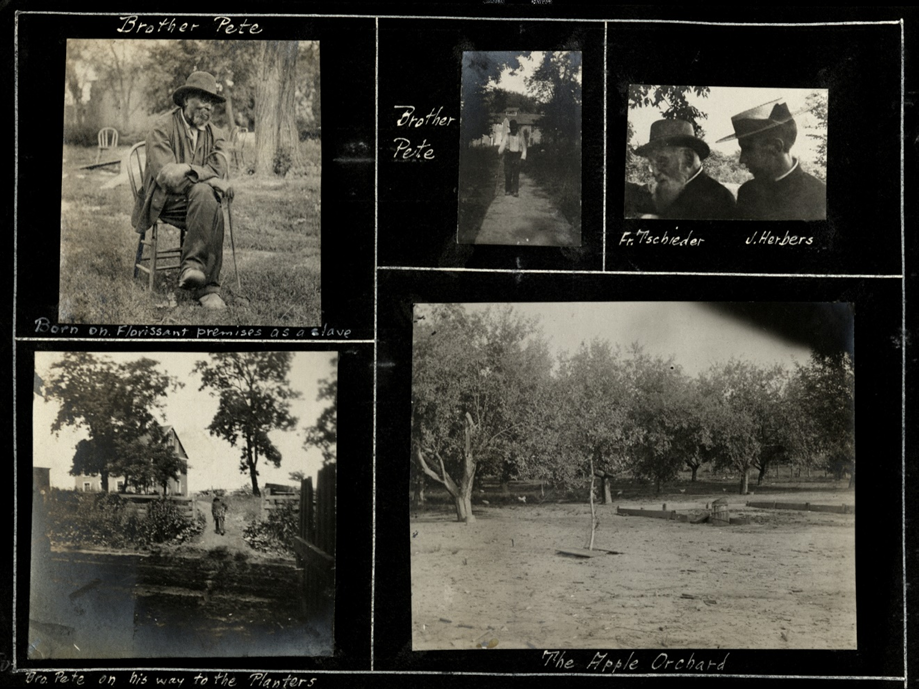

Searching Jesuit archives beyond the scope of enslavement has revealed valuable sources about enslaved experiences, from Jesuit memoirs and histories reflecting upon their interactions with enslaved people to records documenting labor contracts with formerly enslaved families who remained on their farm after abolition, to photographs of former bondspeople in Jesuit scrapbooks, and accounts of encounters with formerly enslaved people in Jesuit memoirs. While Jesuit records continued to document the presence of Peter Hawkins, who remained on the Jesuits’ farm after emancipation, only parish sacramental records track the family of Henrietta Mills-Chauvin, who left Saint Louis University after they obtained freedom but remained parishioners of Jesuit churches. Learning about her life required looking beyond Jesuit archives.[31]

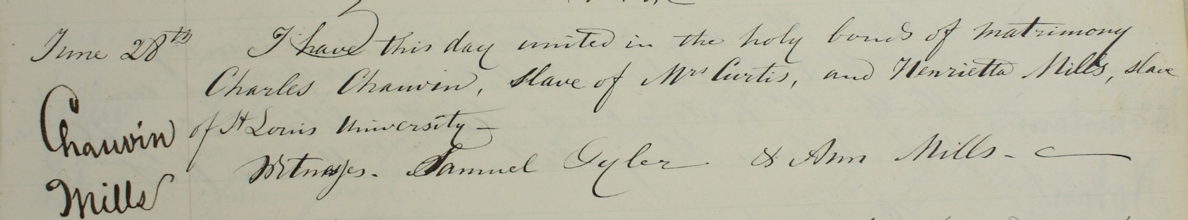

Figure 7. Page from the scrapbook of William Grace, S.J., containing three photographs he had taken of Peter Hawkins c.1905, which he has labeled “Brother Pete: Born on Florissant premises as a slave.” Peter Hawkins was the first enslaved child born on the Florissant plantation, and one of the last formerly enslaved people to remain.

Henrietta Mills may have remained unknown had only Jesuit institutional records from the era of slavery been scoured. Only two surviving sacramental records document her life in slavery, neither of which was found in the Jesuit Archives or the Saint Louis University Archives. The first record found for Henrietta Mills was located in the Archdiocese of Saint Louis Office of Archives and Records, where her June 28, 1860 marriage record to Charles Chauvin in the sacramental registers of Saint Francis Xavier College Church identifies her as a “slave of Saint Louis University,” and Charles as “slave of Mrs. Curtis.” Typically, where Henrietta and Charles were labeled by ownership, marriage records for white couples listed their parents. If the recording Jesuit had denoted her simply as “black” or “Ethiopian,” as he had in other records of this volume, we would never know that Saint Louis University owned her. She has not been found in college financial or administrative records. Her name appears again while in slavery only in her confirmation record of 1855, also stored in the archives of the Archdiocese of Saint Louis.[32]

Figure 8. Marriage record of Henrietta Mills, “slave of Saint Louis University,” to Charles Chauvin.

Using just these two records, we can only surmise what Henrietta Mills-Chauvin’s life was like: that she loved, that she married, that she toiled, that Catholicism played some role in her life. We do not know what she thought, what she dreamed of, what she fought for. But then we continue to expand where we look for records beyond Jesuit archives and beyond enslavement. We find archdiocesan sacramental records for the baptisms of her children, and federal census records demonstrating that Henrietta and her husband Charles had ten children, their first, Sylvester, born five months after their marriage. From federal military records, we learn that Charles Chauvin was drafted as a soldier in the Civil War in November 1864 and advanced through the ranks to become a sergeant, and that Henrietta, in the year of his absence, worked hard to support her two young sons, with census records and city directories showing that poverty persistently threatened them.

As the family persevered through hardship, they led meaningful lives. After Charles returned from war, he and Henrietta named two of their sons Abraham and Lincoln (“Link” for short), presumably in celebration of the freedom they had obtained. When Charles died, Henrietta and her children together strove to support the family. As she applied for Charles’s military pension, Henrietta knew where the records proving her relationship to Charles and the ages of her two youngest dependent children were kept. She went to the Jesuit pastor of Saint Elizabeth parish, who supplied copies of her marriage record and the baptism records of Jerome and Louis and testified to their veracity. Henrietta cited in her pension claim that she was “wholly dependent upon her own labor for her support and for the support of her children, she having no other means of support other than her own daily labor, and that she does not possess any real estate.” To support herself and her two youngest sons, Henrietta worked as a washer and housekeeper, while her elder daughters and sons took up work as teamsters, housekeepers, waiters, washers, and barbers around the city. Yet their labor alone did not define them. Sylvester Chauvin played third base and right field for the Saint Louis Black Stockings, the first professional African American baseball team in Saint Louis and the country. The team was co-founded by Charles H. Tyler, whose mother, Matilda Tyler, and brothers Thomas, Samuel, Edward, and George Jr., previously mentioned, had purchased his freedom from the Jesuits when he was four years old.[33]

Music filled the lives of the Chauvin family. Federal census records, Saint Louis city directories, and an oral history interview show that brothers Sylvester, Abraham, Peter, Link, and Louis Chauvin were musicians. Sylvester played brass instruments, Link played guitar, and Louis played piano. Louis, the youngest, was baptized Louis Ignatius Chauvin in 1884, perhaps indicative of the impact the Jesuits’ Ignatian tradition had left on their lives, both in bondage and in freedom, as they transitioned from the “Negro chapel” in the Jesuit-run Saint Francis Xavier College Church to Saint Elizabeth when it was established in 1873.[34]

Louis Chauvin became the most famous musician of all his brothers. He performed with Scott Joplin and played with Sam Patterson at the 1904 Saint Louis World’s Fair, earning a prize for his music at the Rosebud Café. Louis could not read or write music, and never played the same song twice. Thus, “Heliotrope Bouquet,” which Joplin wrote down, is Chauvin’s only surviving composition. If “Chauv,” as his friends called him, had recorded his music, some ragtime historians assert, we might remember him more than Joplin today.[35]

By piecing together these disparate archival records, we learn about the richness of the Chauvins’ lives. Prior to this, ragtime historians have only speculated about Louis’s parentage. Some have thought his brother Sylvester was his father due to their difference in age, musical background, and shared residence. His friend and fellow musician Sam Patterson believed Louis’s parents were French Creoles from New Orleans. Other publications have projected that Louis’s mother was African American and his father had Spanish and native American ancestry. Without Henrietta Mills’s marriage record from Saint Francis Xavier College Church, denoting her as a “slave of Saint Louis University,” and without Louis’s baptismal record from Saint Elizabeth’s parish naming his parents, we would never know that ragtime musician Louis Chauvin’s family had once been held in bondage to a Jesuit university.[36]

Conclusion

Records about enslaved people in Jesuit sources are plentiful but not foregrounded because enslaved people were not usually the purpose or subject of Jesuit recordkeeping. Rather, Jesuits kept records about their own governance and missionary work and structured their archives and publications accordingly. Records about enslaved people thus usually survive not out of an intent or interest in documenting their lives, but more as a product of Jesuit daily operations, whether those be manual labor or ministry. Memory has further masked the presence of those records and the stories they tell—a subject to be examined more fully in a future essay. From these disparate and forgotten records, however, we can today draw together rich accounts about the lives of the people enslaved to the Jesuits, despite the fact that in the past, having this information scattered across records has tended to obscure the story.

Notes

[1] “Slaves and Slavery,” 1833–1954, Box 3.0134, Folder 9. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection. Jesuit Archives and Research Center, Saint Louis, Missouri (hereafter JARC); “Bill of Sale of Mary,” October 28, 1850, Box 3.0223, Folder 7: Slavery 1850, 1862, 1872. Saint Louis University Collection, JARC; “Bill of Sale for Margaret,” December 26, 1862, Box 3.0223, Folder 7, Slavery 1850, 1862, 1872. Saint Louis University Collection, JARC.

[2] The following is just a selection of the growing scholarship on Jesuit slaveholding: Thomas Murphy, Jesuit Slaveholding in Maryland, 1717–1838 (New York: Routledge, 2001); Sharon M. Leon, “Jesuit Plantation Project”; https://jesuitplantationproject.org/s/jpp/page/welcome (accessed September 1, 2020); Rômulo da Silva Ehalt, “Jesuit Arguments for Voluntary Slavery in Japan and Brazil,” Revista brasileira de história 39, no. 80 (April 2019): 87–107; Matteo Ricci, Della entrata della Compagnia di Giesù e Christianità nella Cina, ed. Piero Corradini and Maddalena del Gatto, trans. Nicholas Lewis and Philip Gavitt (Macerata: Quodlibet, 2000); Brendan J. M. Weaver, “Perspectivas para el desarrollo de una arqueología de la diáspora africana en el Perú: Resultados preliminares del proyecto arqueológico haciendas de Nasca,” Allpanchis 44, no. 80 (2012): 85–120; Weaver, “Rethinking the Political Economy of Slavery: The Hacienda Aesthetic at the Jesuit Vineyards of Nasca, Peru,” Post-medieval Archaeology 52, no. 1 (2018): 117–33; Yannick Le Roux, Réginald Auger, and Nathalie Cazelles, Loyola, les jésuites et l’esclavage l’habitation des jésuites de Rémire en Guyane française (Quebec: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2009); Sherwin K. Bryant, “Enslaved Rebels, Fugitives, and Litigants: The Resistance Continuum in Colonial Quito,” Colonial Latin American Review 13, no. 1 (June 1, 2004): 7–46.

[3] Louis Barada, “Bill of Sale for Peter,” May 1, 1832, Box 3.0136, Folder 26, “Office of Indian Affairs Regarding Saint Francis Indian Seminary, 1819–1832.” Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Deeds of Emancipations,” January 29, 1859, Box 3.0266, Folder 6, “Property Management.” Saint Louis University Collection, JARC.

[4] Paul Nelles, “Jesuit Letters,” Oxford Handbook of the Jesuits, June 12, 2019; https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190639631.013.3 (accessed September 1, 2020).

[5] Markus Friedrich, “Jesuit Bureaucratic Practices and Their Place in the Early Modern History of Knowledge,” paper given at the 2019 International Symposium on Jesuit Studies, “Engaging Sources; The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus,” Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Boston, 2019; Nelles, “Jesuit Letters.”

[6] Margaret’s bill of sale is described in the opening paragraph of this article. Paul Nelles, “Spiritual Accounts: Jesuit Record-Keeping and Early Modern Communication,” paper given at the 2019 International Symposium on Jesuit Studies, “Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus,” Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Boston, 2019; Pierre-Jean de Smet, “Status temporalis, Vice Province of Missouri,” 1862, Folder D, volume 8. De Smetiana, JARC; “Register of Marriages, 1813–1862”; “Register of Burials, 1822–1876,” 1876 1813, Box 3.0373, item 38. Saint Ferdinand Parish Collection, JARC.

[7] Paul Shore, “Voices of Memoria: Diaria, Historiae, and Annuaria as Records of Jesuit Experience,” paper given at the 2019 International Symposium on Jesuit Studies, “Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus,” Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Boston, 2019; Nelles, “Jesuit Letters,” 53.

[8] Kathleen Schmitz and Kelly Schmidt, trans., “Diarium domus probationis in Missouri,” 1835–60, Box 3.0137, vol. 1. Saint Stanislaus Collection, JARC; Richard H. Clarke, Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States, Volume 2 (New York: R. H. Clarke, 1872); John Gilmary Shea, A History of the Catholic Church within the Limits of the United States, from the First Attempted Colonization to the Present Time (New York: J. G. Shea, 1886); Joseph L. J. Kirlin, Catholicity in Philadelphia: From the Earliest Missionaries down to the Present Time (Philadelphia: J. J. McVey, 1909); Joseph M. Flynn, The Catholic Church in New Jersey (Morristown, NJ, n.p., 1904); F. [Fielding] Lucas, The Metropolitan Catholic Almanac and Laity’s Directory (Baltimore: F. Lucas Jr., 1855); Francis P. Nussbaum, “Diarium Universitatis Sti. Ludovici,” 1855–82, Doc. Rec. 001 0024 002, Saint Louis University Historical Records, Saint Louis University Archives and Special Collections (hereafter SLU).

[9] Nicholas Lewis and Kelly L. Schmidt, trans., “Minister’s Diary, Saint Charles College,” n.d., unprocessed collection, New Orleans Province Archive, JARC.

[10] Nelles, “Spiritual Accounts”; Nelles, “Jesuit Letters,” 51; Markus Friedrich, “Circulating and Compiling the Litterae annuae: Towards a History of the Jesuit System of Communication,” Institutum historicum Societatis Iesu 77 (2008): 3–39.

[11] “Litterae annuae,” 1858–59, Box 3.0226, Folder 2. Saint Louis University Collection, JARC; “Historia domus probationis Sti Stanislai,” 1871–74, Bin 3.0148, Folder 27. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Historia domus probationis Sti. Stanislai […] Per annos scholares,” 66, 1866–67, 1867–68 1865, Box 3.0148, Folder 26. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Historia domus probationis Sti. Stanislai […] Per annos scholares,” 66, 1866–67, 1867–68, 1865, Box 3.0148, Folder 27. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Litterae annuae,” 1845, Box 3.0148, Folder 26. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection. JARC; “Confirmations and Communions, 1824–1918” (Saint Ferdinand parish, 1824–1918); Shore, “Voices of Memoria.”

[12] Shore, “Voices of Memoria”; Nelles, “Jesuit Letters,” 53; Friedrich, “Circulating and Compiling the Litterae annuae.”

[13] “Litterae annuae Sti. Stanislai,” July 1868, Box 3.0148, Folder 26. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Litterae annuae Sti. Stanislai,” July 1868, Box 3.0148, Folder 27. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC.

[14] Thomas J. Morrissey, As One Sent: Peter Kenney, S.J. (1779–1841) (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1996); Robert Emmett Curran, “Peter Kenney: Twice Visitor of the Maryland Mission (1819–21, 1830–33) and Father of the First Two American Provinces,” in With Eyes and Ears Open: The Role of Visitors in the Society of Jesus, ed. Thomas M. McCoog (Boston: Brill, 2019), 191–213, here 195, 197, 205.

[15] “Tertius liber archivii domus probationis Sti. Stanislai missionis S.J. Missourianae,” 1832–73, Bin 3.0148, vol. 3. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; Curran, “Peter Kenney.”

[16] “Tertius liber archivii domus probationis Sti. Stanislai missionis S.J. Missourianae,” 1832–73, Bin 3.0148, vol. 3. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; Curran, “Peter Kenney.”

[17] “Tertius liber archivii domus probationis Sti. Stanislai missionis S.J. Missourianae”; Morrissey, As One Sent, 303; Nelles, “Spiritual Accounts”; “Saint Joseph’s College, Financial Records,” 1848–56, Doc. Rec. 001 0033 0003, SLU; “Saint Joseph’s College Financial Records,” 1849–61, Doc. Rec. 001 0033 0004, SLU; “General Charge and Discharge Book, 1831–1881,” Box 3.0145, vol. 1. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Ledger of Saint Stanislaus House, 1840–1857,” Box 3.0146, vol. 1. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Day Book Volume 4,” 1848–54, Box 3.0143, vol. 4. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “General Charge and Discharge Book and Ledger of the House of Saint Stanislaus,” 1838–68, Bin 3.0145, vol. 3. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Ledger of the Missouri Mission, 1836–1851,” Box 2.0157, vol. 5. Office of the Treasurer Collection, JARC.

[18] Friedrich, “Jesuit Bureaucratic Practices and Their Place in the Early Modern History of Knowledge”; Nelles, “Spiritual Accounts”; Friedrich, “Circulating and Compiling the Litterae annuae.” See also: Robert Emmett Curran, Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2012).

[19] “Slaves and Slavery,” JARC.

[20] “Letterbook and Property Inventory,” 1852–58, Box 2.0018, vol. 1. General Governance Collection, JARC; Edward R. Vollmar, “The Archives of the Missouri Province of the Society of Jesus,” Manuscripta 12 (1968): 179–89, here 181.

[21] “Letterbook and Property Inventory,” 1852–58, Box 2.0018, vol. 1. General Governance Collection, JARC; Vollmar, “Archives of the Missouri Province,” 181; “Missouri Province Archive”; http://jesuitarchives.org/collections/missouri-province-archive/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

[22] Vollmar, “Archives of the Missouri Province”; Gilbert J. Garraghan, The Jesuits of the Middle United States (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1938), 613.

[23] Therese Meyerhoff, “Jesuit Archives & Research Center Is Blessed,” Jesuits Central and Southern, August 23, 2018; http://jesuitscentralsouthern.org/news-detail?TN=NEWS-20180823030628 (accessed September 1, 2020).

[24] “Day Book, 1831–1838,” Box 3.0143, vol. 2. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Receipts and Expenditures, 1841–1850,” Box 3.0146, vol. 11. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Saint Joseph’s College Financial Records,” 1849–61, Doc. Rec. 001 0033 0004, SLU; “Ledger of the Missouri Mission, 1836–1851,” Box 2.0157, vol. 5. Office of the Treasurer Collection, JARC; For more on kinship patterns traced through sacramental records, see Kelly L. Schmidt, “Enslaved Faith Communities in the Jesuits’ Missouri Mission,” U.S. Catholic Historian, Church and Slavery, 37, no. 2 (Spring 2019): 49–82.

[25] William Stack Murphy to Jan Roothaan, October 8, 1851, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (hereafter ARSI); “Consultors Meeting Minutes for the Missouri Vice Province,” Missouri Province Archive, JARC; Peter Verhaegen, “$50 Reward,” Louisville Daily Courier, November 13, 1849.

[26] Felix Verreydt, “Memoirs,” c.1870, Felix Verreydt Personnel File, JARC; Walter Hill, “Autobiography in Three Parts,” n.d., Walter Hill Personnel Files, JARC; Theodore de Theux to Jan Roothaan, January 16, 1831, ARSI; Peter Verhaegen to Jan Roothaan, September 7, 1830, ARSI; Peter Verhaegen to Jan Roothaan, August 25, 1832, Missouri Province Collection, ARSI; Pierre-Jean de Smet to Peter Verhaegen, June 11, 1830, Maryland State Archives film about Missouri mission/province, MSA M 1320, JARC.

[27] Verreydt, “Memoirs”; Hill, “Autobiography in Three Parts”; Theodore de Theux to Jan Roothaan, January 16, 1831, ARSI; Peter Verhaegen to Jan Roothaan, September 7, 1830, ARSI; Peter Verhaegen to Jan Roothaan, August 25, 1832, Missouri Province Collection, ARSI; Pierre-Jean de Smet to Peter Verhaegen, June 11, 1830, Maryland State Archives film about Missouri mission/province, MSA M 1320, JARC; Thomas Brown, October 21, 1833, Maryland Province Archives; Morrissey, As One Sent, 285–86, 304–5; “Tertius liber archivii domus probationis Sti. Stanislai missionis S.J. Missourianae,” 1832–73, Box 3.0148, vol. 3. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC.

[28] “House Treasurer’s Inventories,” 1824–71, Bin 3.0148, Folder 6. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC.

[29] Adam Marshall, “Transfer of Slaves by Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland to Father Charles Felix Van Quickenborne, Contract,” April 10, 1823, Box 2.008, Folder 1. General Governance Collection, JARC; “Missouri Mission Varia,” n.d., Box 2.0157, item 2. Office of the Treasurer Collection, JARC.

[30] The families of Isaac and Susan and Proteus and Anny appear in records sometimes with the surname Queen, and at other times with the surname Hawkins, though Hawkins appears to be their formal surname. The families and the Jesuits used these surnames interchangeably, possibly because the Queens and Hawkinses were closely connected by marriage (as suggested by the marriage record between Isaac Hawkins and Susanna Queen in 1823). Adam Marshall, “Transfer of Slaves by Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland to Father Charles Felix Van Quickenborne, Contract,” April 10, 1823, Box 2.008, Folder 1. General Governance Collection, JARC; “Missouri Mission Varia,” n.d., Box 2.0157, item 2. Office of the Treasurer Collection, JARC; “Cloth Expenses,” 1831–36, Box 3.0135, Folder 13. Saint Stanislaus Seminary Collection, JARC; “Old Saint Ferdinand Records, 1792–1856” (Saint Ferdinand parish), Archdiocese of Saint Louis Office of Archives and Records (hereafter ArchStL); “Ledger, 1814, 1850s Baptisms,” 1814–65 (Saint Ferdinand parish), ArchStL; “Confirmations and Communions, 1824–1918” (Saint Ferdinand parish), ArchStL; “Baptism Records, 1855–1899” (Saint Ferdinand parish), ArchStL; “Record of Marriages, 1863–1898” (Saint Ferdinand parish), ArchStL; “Register of Baptisms, White Marsh,” 1818–22 (Georgetown Slavery Archive), Maryland Province Archives.

[31] Verreydt, “Memoirs”; Hill, “Autobiography”; “Letter from the Novitiate, Florissant,” Woodstock Letters 1 (November 24, 1871), JARC, 38-45; William J. Grace, “Photographs of Brother Peter, in Album 25, Scrapbook by William J. Grace, S.J.,” 1905, Box 2.0125. Missouri Province Scrapbook Collection, JARC; William Markoe, “Memoirs: An Interracial Role,” William Markoe Personnel File. Personnel Files, unprocessed collection. JARC.

[32] “Baptismal Record, July 1840 to June 1856” (Saint Francis Xavier College Church), ArchStL; “Confirmations, First Communions, Members Lists, 1846–1872” (Saint Francis Xavier College Church, 1872, 1846), ArchStL.

[33] “Baptisms, Volume 1, 1860–1872” (Saint Elizabeth parish), ArchStL; “Baptisms, Volume 2, 1870–1906” (Saint Elizabeth parish), ArchStL; “Tenth Census of the United States for Saint Louis, Missouri” (microfilm publication T9, 1880), Roll 720, p. 64C, National Archives and Records Administration; “Tenth Census of the United States for Saint Louis, Missouri” (microfilm publication T9, 1880), Roll 730, p. 82B, NARA; Saint Louis City Directories, 1865–84; “Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, Including the 11th (New),” 1864–65, M1821 Roll 77, National Archives and Records Administration; Henrietta Chauvin Pension Claim, 1890, NARA; “Diamond Dust,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, May 8, 1883; “The Colored Champions Win,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, May 8, 1883; James E. Brunson III, The Early Image of Black Baseball: Race and Representation in the Popular Press, 1871–1890 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009); Brunson, Black Baseball: A Comprehensive Record of the Teams, Players, Managers, Owners, and Umpires, 3 vols. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2019), 135, 324; Circuit Court Record Book, 18:416, 18:447, Missouri State Archives-Saint Louis; “Ledger of the Missouri Mission, 1836–1851,” JARC.

[34] 1900 Federal Census for Saint Louis, Missouri, NARA; Saint Louis City Directories, 1883–1916; Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, interview with Sam Patterson, New York, November 1949; “Baptisms, Volume 2, 1870–1906” (Saint Elizabeth parish, 1870–1906), ArchStL; “The Rose Bud Ball,” Saint Louis Palladium, December 24, 1904; Edward A. Berlin, King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); for more on the transition of black Catholics from Saint Francis Xavier College Church to Saint Elizabeth’s parish, see Jeffrey R. Dorr, “Race in Saint Louis’s Catholic Church: Discourse, Structures, and Segregation, 1873–1941” (master’s thesis, Saint Louis University, 2015); Schmidt, “Enslaved Faith Communities in the Jesuits’ Missouri Mission.”

[35] Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, interview with Sam Patterson, New York, November 1949; “Rose Bud Ball,” Saint Louis Palladium, December 24, 1904.

[36] Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, interview with Sam Patterson, New York, November 1949; “Rose Bud Ball,” Saint Louis Palladium, December 24, 1904; Berlin, King of Ragtime; Brunson, Early Image of Black Baseball; Brunson, Black Baseball, 135, 324; Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime, revised ed. (New York: Oak Publications, 1974).